“Hello. My name is Joel. I am from the United States of America. I speak English. I do not speak Lao. If you want to say something about me, and you do not want me to understand, you can say it in Lao. You can call me smelly, ugly, or stupid, as long as you say it in Lao, you will have no problems, because I will not understand.”

“Hello. My name is Joel. I am from the United States of America. I speak English. I do not speak Lao. If you want to say something about me, and you do not want me to understand, you can say it in Lao. You can call me smelly, ugly, or stupid, as long as you say it in Lao, you will have no problems, because I will not understand.”And that's how I started my first-ever English class. I knew a lot of the students were more advanced than the others, and I got a pretty good idea of who was who by watching who was laughing at this point.

I'd never seen an English class taught before. I have no training as a teacher, in any subject. But I speak English, I was in the area, willing to volunteer, and that seemed to be enough.

My father once told me that in medical school, the usual phrase for any procedure was “See one, do one, teach one.” I glanced over at another travel blog and saw that the procedure for learning how to teach English classes in Taiwan shortened this to “see one, teach one.” Here in Vang Vieng, Laos, that was a bit much. My teacher training program? “Teach one.”

The program is based out of an organic farm in Vang Vieng. I came to a morning meeting and presented myself to the four-person office (two of which were foreign volunteers like me). They handed me a thin paperback textbook (Thai-English rather than Lao-English), opened to the pages I would be teaching, said the “read aloud” phrases should be read aloud and that the questions on the next page should be answered with the books closed. I tried to clarify who was supposed to be reading what and the Belgian director just said “up to you, man. However you want to do it.” After working at it a bit, I got a couple more tips on how he would teach the class, but I still felt like I'd been tossed in a kitchen, asked to make a soufflé, and upon any questions about how to keep a soufflé from collapsing was simply told “up to you, man. However you want to do it.”

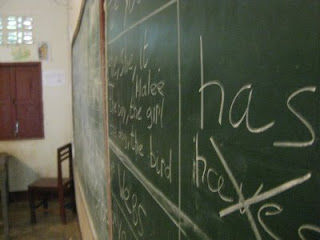

I biked to the school around five. The classroom was just like you picture them in all the volunteer brochures for teaching or building schools in the third world. There were dirty, bare, whitewashed walls, unpainted wooden benches and tables, a chalkboard that was half white from chalk dust, and windows with no glass opening to the outside yard.

I felt like only half the class was paying attention at any given time. I had an especially hard time getting the boys, who were all sitting in the back of the classroom, to look up. We read the pages, I wrote on the chalkboard. Since they were all too shy to raise their hands, I picked specific kids to read sentences or answer my questions (usually I picked whoever seemed to be paying the least attention at the time) though near the end, some kids started getting sly grins and pointing at their neighbors when I asked “who wants to read the next one?”

By the time we were finishing the last page, only about half an hour of the assigned hour was up. I made up more questions, went back over the material they had learned last class, and went over new vocabulary. “Little” was very easy to explain. So was “how old,” many of them seemed to already know it. But I faltered a bit when I realized I had to try to explain the word “how” by itself to kids who, when asked “would you please read number five,” would occasionally get the bewildered half-smile you get when you aren't sure if what was just said was supposed to be a joke.

I stumbled through it, asked a student what time it was, and let them all out about ten minutes early. They still sat there. I think there was supposed to be a specific phrase told to them like “you may go,” or “class dismissed,” so I tried a couple, and one of them must have worked, but they kept hesitating when I tried more or said more because if the teacher was still talking, they were clearly supposed to be paying attention. Finally they cleared out, smiling, laughing, some of them yelling “thank you, teacher” and filing out, some of them closing the windows as they did.

I looked around for something teacher-like to do, not having been told how to close up the room. I erased the chalkboards with the stuffed fabric bag the class pointed out to me after I'd been erasing stuff with my hand, turned off the lights, and stepped outside, closing the door behind me. I kept a slight distance from the retreating students, remembering how awkward it was when my elementary school teachers insisted on existing outside the classroom. I got on my borrowed bike and pedaled back to the organic farm's guesthouse.

It wasn't really until I got back that I got a taste of what everyone said made the job so rewarding. It was when I was putting away the bike and casually said Sabai-Dee (hello) to one of the farm employees. That was it. In that moment, I was no longer a traveler greeting someone of the staff, I was one member of the community saying hello to another. I'd slipped into the part of the village teacher- educated, kindly, somewhat solitary, possibly a bit eccentric, riding my bike to and from school as people on motorcycles and in trucks passed and waved. I wasn't just a foreigner passing through, I was here doing something.

The rainy season has started here but I was still pretty warm. I went back to my dorm, put my swimming shorts on, and jumped into the river. The current swept me downstream just a few hundred meters into the completely different world that Vang Vieng is famous for: tubing.

Tubing means renting a tractor-sized inner tube, floating down a river, and, here in Vang Vieng, getting indulging in either adrenaline off the ziplines, trapezes and water slide into the rushing water, getting plastered with mud in a mud pit,or doing what most people do and getting plastered off of Beerlao, lao lao rice whiskey (free shots), or bright-colored sand pails full of cocktails. Or other things. I saw at least one place with a sign offering a free beer if you buy a joint. Shrooms can be found as well, and I know even opium is available in town. I stuck to the adrenaline-- general principle, plus I had kids to teach again the next day.

I take a particularly dim view of opium here, considering that it brought the region to its knees not that long ago, historically speaking. Now all these foreigners (because only foreigners go tubing) are showing it as being popular to the young Lao. It's not just here while tubing either. In every Lao city I've been to, every tuk-tuk (motorcycle-rickshaw taxi) will have a driver who will shoot undertone offers of weed, opium, shrooms, women, and whatever else they think I must want as I walk by. I thought about keeping a tally at one point of what I was offered the most often, but I've long since lost track.

So while I still have a lot of fun ziplining and flying with a trapeze into a fast river, I'm staying as far from the scene as I can get. I know this might disappoint some people, but I've had enough of the music they're blasting (it's the exact same technopop soundtrack the followed me through every hostel in Australia: Pokerface- The Sex is On Fire- The Love is Gone-etc etc.) and I'm tired of being offered opium when all I want is a sandwich. I heard about this organic farm 3 km from town, near where the tubers (what I like to call those of us doing it) used to start tubing. It's got everything a guilt-ridden western traveler would love to brag about: organic food, all proceeds going to good local causes, volunteer opportunities both in the farms, and in local English classes (how I got my gig teaching). I fixed a couple computer problems in the school office, and now get to use their internet from time to time.

Today's class went better than yesterday's-- I got them on their feet and playing some games, learning the word “borrow”, and then splitting them into two teams racing to “borrow” a plastic baseball bat to get it across the room, one teammate at a time. Then I got them all laughing by lying down on my back, looking at the ceiling while explaining the concept of perspective (mostly because I didn't feel like making them memorize and recite the only thing written on that page of their textbook: “Giant why are you so tall?”/Well sir, why are you so small?”). Then we had some activities with simple family trees until I ran out of time. I'm starting to see how so many people get hooked on teaching English out here.

It's really impressive how skewed your perspective can get when your normal life consists of doing things like waking up in an organic farm, swinging on a high trapeze into a river and then teaching English to Lao schoolkids before coming back for a homemade tom yum soup for dinner. I talk to people who discuss the best times to see world heritage landmarks the way I used to discuss how to go see a grocery store. David Sedaris described it really well when comparing his childhood to that of an boyfriend who grew up in Africa. All the verbs were the same. It was just the nouns that came out different. Instead of eating spaghetti at the cafeteria, sipping on root beer, I'm eating fresh spring rolls at a stall next to the Mekong River, sipping a fresh coconut. My 23rd birthday is in exactly one month. Usually I'd wonder which place in the city I'd celebrate. Now I'm wondering which country I'll be in. I guess that's travel.

---

Check out this entry's Photos.

Questions? Comments?

Questions? Comments?

Hey Joel,

ReplyDeleteIt sounds like Vang Vieng has gotten druggier since when I was there. That's too bad; the whole "tube for a bit, have a drink, swing into the water, tube some more" thing was a lot of fun."

I assume you'll be in Luang Prabang before long. Two notes - don't buy rice from the ladies who try to sell it to you so you can give it to the monks in the morning; they make it really kitschy and that's no fun. Getting the monks rice is definitely worth doing, but try to avoid doing it near a hotel, and try to buy the rice ahead of time so you don't have them breathing down your neck.

Second, I forget the name of the hill, but whatever the hill in the middle of Luang Prabang is called - go up it to catch a sunrise or a sunset. Believe me, it's worth it.

Keep on rockin' in the (not) free world,

Jordan Phillips

Teaching language is fun! And the more you can get away from the books and get your students doing things, the more fun it gets. That's how we all learned as kids, after all, just listining to people talk about stuff and tell us what to do, and trying to figure out what the heck they were saying (No, dear, give me the red ball. Not the blue one the red one).

ReplyDeleteThe post was very interesting and combined with the pictures was terrific. Nice variety of images and range.. with people, landscape, food, interesting signs etc. give such a sense of the whole. The picture of the fruit was gorgeous! And the goat, pig and geese fun pics.

ReplyDeleteJordan- Actually I went the other way-- loved the sunset from the hill, but I was too thick to hear about the monks and rice until after I'd left! Always got up too late or too early somehow.

ReplyDeleteA lot of people out here are talking about how fast vang vieng has been changing. Mostly they've been talking about buildings going up quickly and moving the tubing start way downriver, but I wouldn't be surprised if someone told me the drug scene has grown. It's pretty big and pretty obvious.

Catherine- It was a tough balance-- I was only there two days and the kids are learning a curriculum that lasts months. So I had to make it good and interesting, yet not reinvent the wheel for them, if that makes sense. Having a new teacher every few days makes things confusing, so even if the book wasn't very good, at least it was reliable.

Anonymous- Thank you very much! I think great photographers can take ordinary things and make them look beautiful. I cheat-- I go to the most beautiful things in the world and take pictures of them. Weirdly enough, they don't come out half bad! Glad you're enjoying them.